Toni Morrison’s Men

Toni Morrison quietly mapped the fraught interior lives of Black men, revealing survival strategies shaped by society, silence, and the longing to be whole.

When we talk about Toni Morrison, we often begin in the interior lives of Black women. We talk about Sethe’s grief. Pecola’s longing. Sula’s defiance. Pilate’s wisdom. And rightly so. But to read Morrison closely is also to encounter a quiet, relentless cartographer of Black masculinity—in the shadows, on the porches, or out on the road.

She did not write us as monoliths. She refused the flat seductions of portraying us purely as innocent victims or unredeemable pathologies. Instead, Morrison observed Black manhood as an exhausting, ongoing negotiation: between fear and desire, between land and sky, between silence and speech, between love and domination.

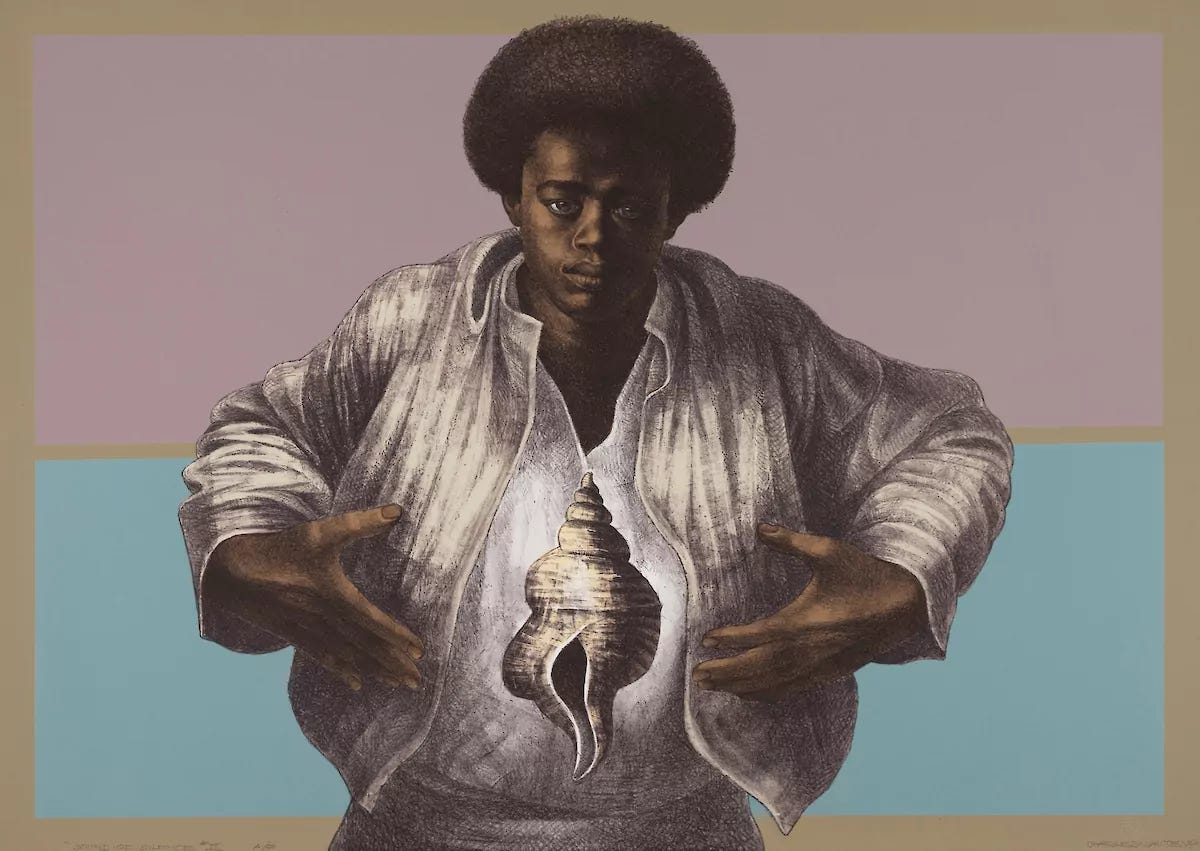

Her men build walls. They sprout wings. They bury their hearts in tins. And the people around them—most often the women and children who love them—live within the blast radius of those survival strategies.

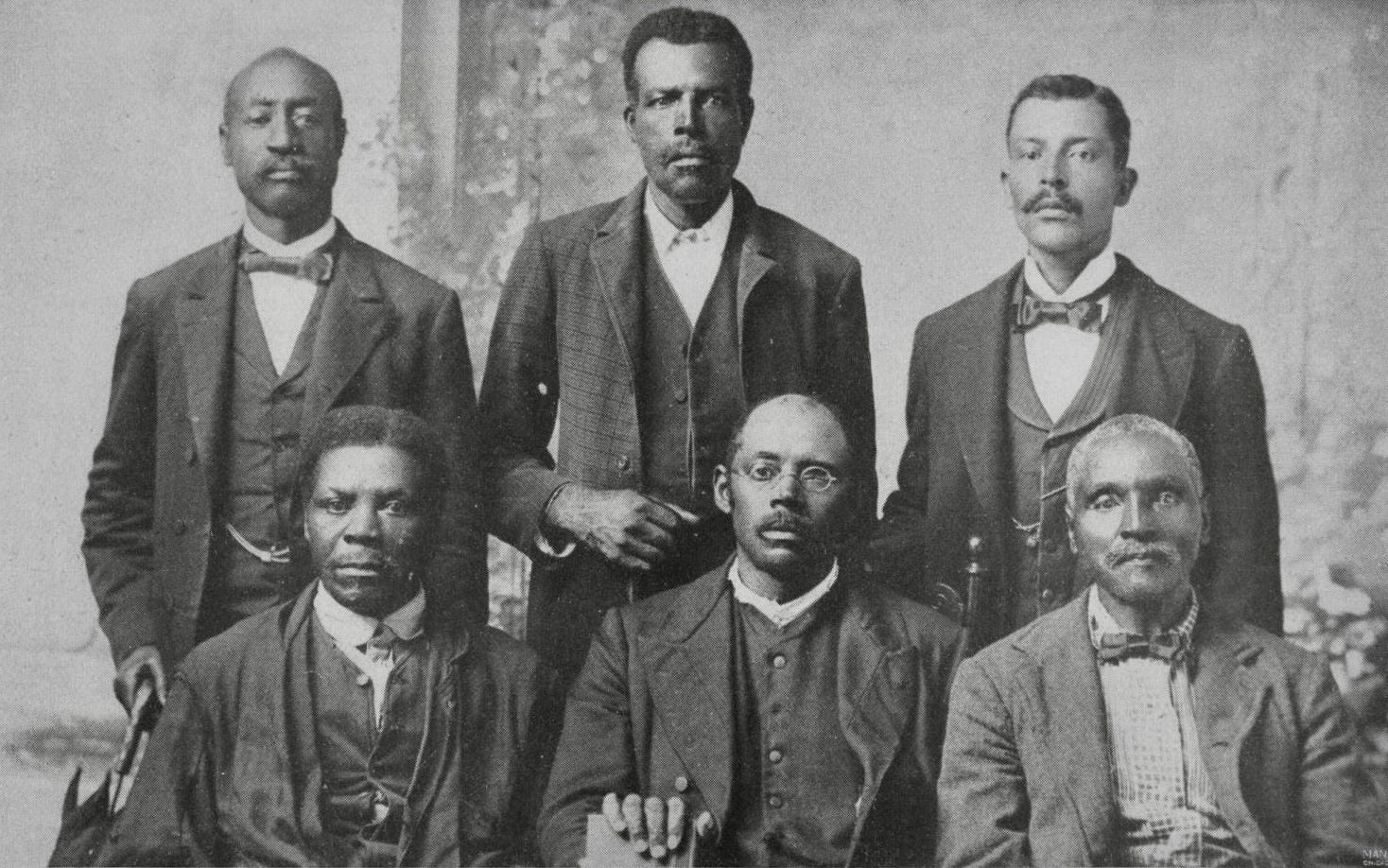

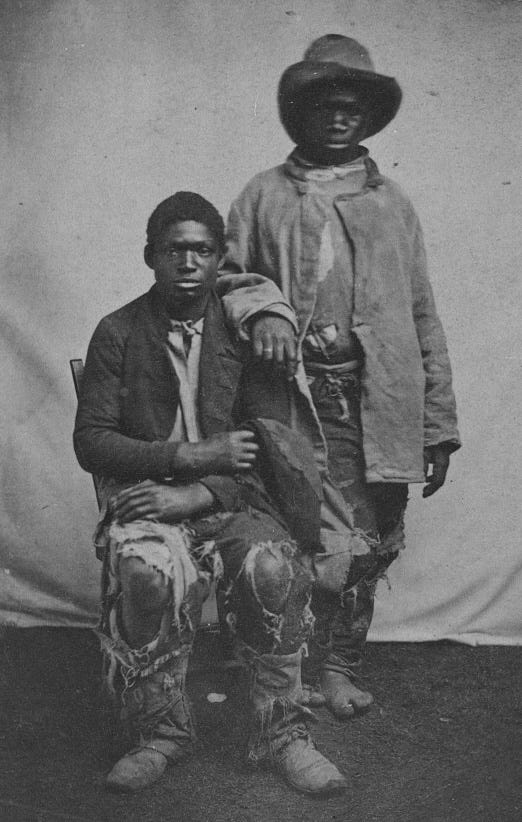

Let’s begin where Morrison insists we must. In Morrison’s America, slavery is never past tense. It is structure. It is blueprint. It is load-bearing. Consider the men of Sweet Home in Beloved—Paul D, Halle, Sixo, Paul A. They are introduced as laborers granted the limited, choreographed freedoms of Mr. Garner’s so-called benevolence. Garner allows them to handle guns. He encourages them to “be men.” But the permission is theatrical. Their masculinity exists only so long as it flatters white ownership. The moment Garner dies and schoolteacher arrives, the illusion collapses. The men are measured, catalogued, reduced to animal traits in a ledger.

Paul D reflects on this theft with devastating clarity: “I wasn’t allowed to be and stay what I was.”

Morrison is making a devastating claim: slavery did not merely brutalize Black boys and men. It dismantled the conditions required for masculinity as Western society defined it—protection, authority, provision, sexual autonomy.

Halle’s undoing is not simply the brutality he witnesses. It is his impotence to stop it. Watching Sethe be violated from the loft, he cannot intervene. His role as “husband” is been rendered structurally absurd, producing a psychic rupture. His mind fractures because his love has been emptied of meaning.

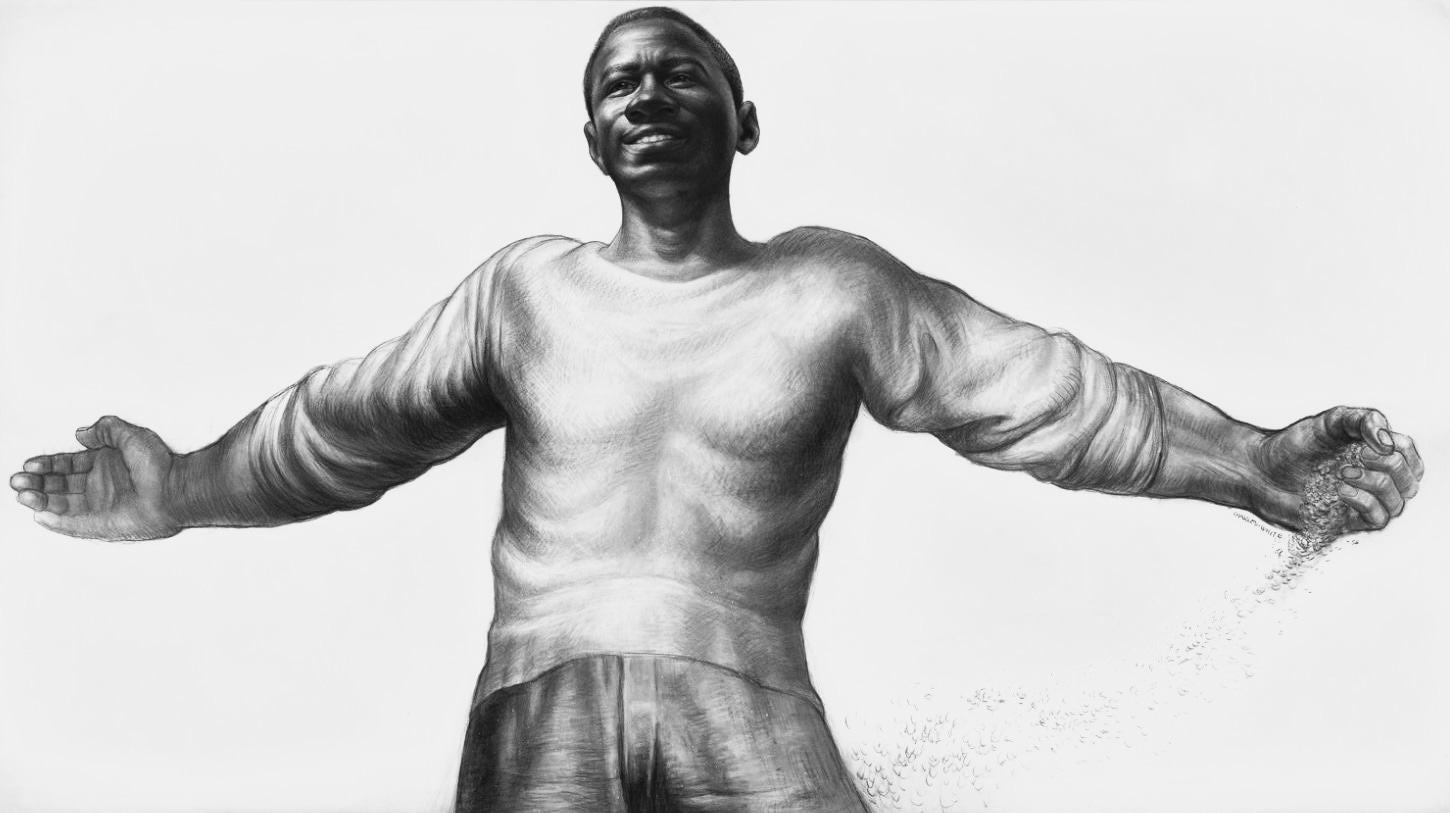

Paul D chooses another strategy. He survives by sealing himself. “He would keep the rest where it belonged,” Morrison writes, “in that tobacco tin buried in his chest where a red heart used to be.” The image is metallic, utilitarian. It is a device. It preserves the body while eroding the self.

This logic of criminalized protection echoes backward and forward through Morrison’s work. In The Bluest Eye, Cholly Breedlove’s adolescence is ruptured by white men who force him to continue a sexual encounter at gunpoint for their amusement. The humiliation curdles. He grows into a father who violates rather than protects. Morrison does something dangerous here: she traces the origin without dissolving the horror. Cholly is monstrous. He is also traceable.

In Home, Frank Money returns from Korea to a country that still treats him as surplus. The military has modernized the plantation wound. He, too, must confront what it means to have been structurally denied the capacity to protect.

Across generations, Morrison suggests that Black masculinity in America begins with interruption—violent, sexual, militarized. That condition is the climate in which her men attempt love, fatherhood, ambition.

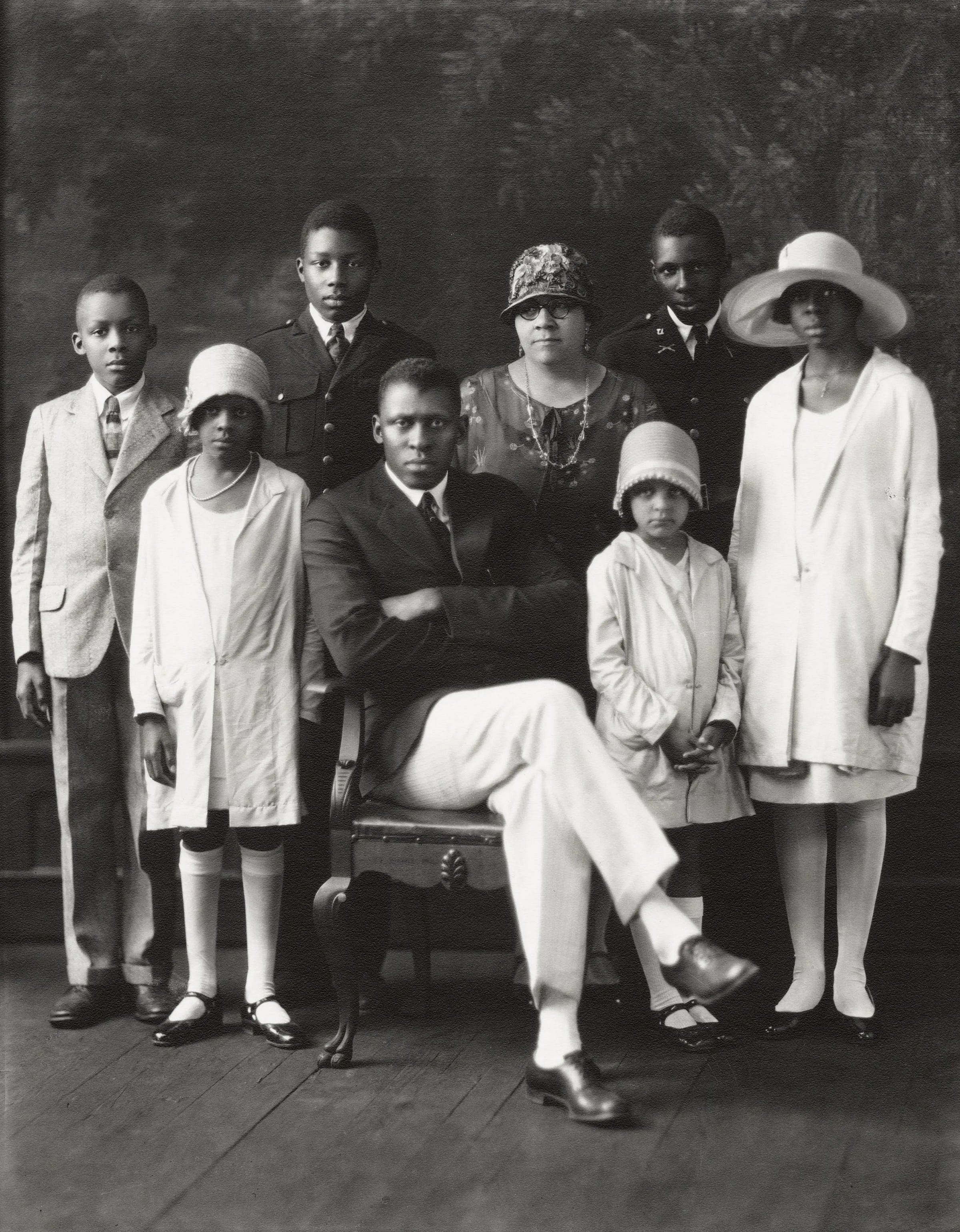

Denied structural authority in the wider world, Morrison’s men often seek power in the intimate sphere. The family becomes the site where systemic emasculation is negotiated, and where its consequences are most acutely felt.

Some men flee, leaving absence as inheritance. Others stay but distort intimacy in an effort to stabilize their own fractured sense of self. In Sula, Jude Greene marries Nel not out of deep partnership but out of hunger for validation. Shut out of meaningful labor on the road crew, he turns toward marriage as confirmation. “The two of them together would make one Jude.” His betrayal is less about desire than about ego under siege. Masculinity, when tethered to external recognition, becomes brittle.

What begins as a private attempt to stabilize the self can expand outward. When ego bruised by racism hardens into ideology, masculinity no longer seeks validation through marriage alone—it seeks it through control.

In Song of Solomon, Guitar Bains joins a secret society committed to avenging racist killings through retaliatory murder. “What I’m doing ain’t about hating white people. It’s about loving us.” Morrison knows how easily love becomes weaponized when fused with rage. Denied justice, Guitar builds symmetry with blood.

And in Paradise, the Morgan twins build Ruby—an all-Black town forged from exclusion. Ruby is fortress theology: purity, discipline, lineage. They believe they are protecting Blackness. But fear curdles. Protection mutates into violence. They massacre the women in the Convent. The master’s blueprint, once internalized, does not disappear. It shrinks to scale.

But domination is not the only response to powerlessness. Some of Morrison’s men reject walls altogether. If one strategy for surviving humiliation is to build fortresses, another is to refuse confinement entirely. And here we arrive at Morrison’s most enduring tension: wings and walls.

Flight is seductive. It promises autonomy, transcendence, relief from suffocation. Song of Solomon is haunted by the legend of an enslaved man who flew back to Africa, leaving his family behind. “O Solomon don’t leave me here.” Flight frees the flyer. It wounds those below.

Solomon’s Milkman leaves to find his origins. Sula’s Ajax drifts without attachment. Tar Baby’s Son refuses assimilation. They resist enclosure. But flight can become abandonment.

Against the wanderers stand the builders. In Solomon, Macon Dead II accumulates property. “Own things,” he tells his son. “And let the things you own own other things.” Walls promise safety. But walls can suffocate love. Morrison sanctifies neither. She shows us that Black men are often caught between two incomplete survival strategies: enclosure or escape.

And what allows both to persist? Silence. Flight avoids explanation. Walls forbid it. Paul D chokes back his history, terrified that speaking it might push him “to a place they couldn’t get back from.” But Morrison does not accept that. Healing, in her universe, is tied to speech. Stamp Paid speaks in Beloved of the history he cannot forget—about slavery and the low places it took him. Frank Money, the protagonist of Home, begins to heal only when he names where he has been and what he has done. Speech risks vulnerability. And vulnerability threatens masculinity constructed through hardness. So Morrison asks a radical question: What would happen if the tobacco tin were pried open?

At the end of Song of Solomon, Milkman leaps toward Guitar in the dark. “If you surrendered to the air, you could ride it.” He could fly. Or he could fall. Morrison refuses to clarify. And that refusal is the point. Black manhood, in her work, is not a solved equation. It is a negotiation—between inherited trauma and chosen action, between sealing the heart and risking tenderness, between building walls and breaking them.

She does not romanticize Black men. She does not demonize us. She insists we are fully human—yearning, contradictory, capable of love and destruction—trying to define masculinity in a nation that has already defined us as surplus. And perhaps that is her fiercest claim: Black men, too, possess interiors worth mapping. Even when sealed in tin. Even mid-flight. Even standing behind walls we built ourselves.

She leaves the leap unresolved. Because the negotiation continues.

Donovan X. Ramsey’s writing explores identity, culture, and power in America. He is the author of When Crack Was King: A People’s History of a Misunderstood Era and Had Happened, a weekly newsletter. His reporting and commentary have appeared in The Atlantic, GQ, The New York Times, and beyond.

This was so good! I studied Toni Morrison's work under Columbia University professor Farah Griffin and we talked at length about the way Morrison wrote black men. They were dynamic, brutal, loving, selfish, and at times both for and against their own but she wrote them fully. Song of Solomon is my favorite Morrison book due to the fact that its a male protagonist and the way she write Milkman is both infuriating but also allows us to see the interiority of the women around him. Anyway great post I enjoyed!

I’m so glad a friend forwarded this essay to me. She sent it because I just published a voice note about masculinity in Beloved last week, and this was the perfect follow up reading. Great work, Donovan!